THE MIRACLE OF WRITING FOR RADIO

by Edgar Farr Russell, III, © 2003

(From Radio Recall, June 2003)

An old Chinese proverb states that a journey of a thousand miles begins with the first step. Is there a voyage of imagination you've wanted to make? Do you have a desire to share with an audience an amazing adventure, a magnificent mystery, or even a captivating comedy? Then, you're a storyteller!

If you’ve resisted bringing your idea to life, is it because you’re not sure how to go about writing it down? Or is it because you don’t have the million-dollar budget to film your epic story? Perhaps television or the stage couldn’t do justice to your vision either. That’s when your thoughts should turn to the Theater of the Mind; better known as Dramatic Radio. Yes, Radio-- where your audience participates in the story to a degree not experienced in any other medium. Radio-- where you may weave your vivid images into unforgettable tapestries of both the familiar and the fantastic-- all at a fraction of the cost!

That’s the reason for the above title. And when you write for radio, you and your audience can experience this miracle together. But how do you begin this journey? What knowledge do you need to start and what must you take with you along the way? Let’s take that first step together.

First, I will offer some considerations for creating the story you want to tell. Then, I will describe the four components of a radio script. Next, I will give a few ideas on how you may get your play read and produced. Finally, I’ll give you some hints on how the producer, director, actors, musicians, sound effects team, and other crew members can share your vision.

To be successful, a radio play should tell a story which interests the audience. This may seem obvious, but it is important to deliver something fresh, which commands attention. Some have argued that there are only seven basic plots. If true, then pick a location or a time that hasn’t already been dramatized to death.

Whether or not you select a frequently used place or period, you’ll still want to offer your audience a stimulating variety of characters-- people that you yourself would like to meet. Know their hopes and dreams. Make your villains as interesting as your heroes and heroines. Give your characters flaws as well as strengths. Perhaps a vicious gangster has a passion for classical music. Maybe an elegantly beautiful ballerina thinks she is really an ugly duckling. Most important, give your characters a goal-- something they want badly-- so badly that they will struggle against all obstacles until they either triumph or consume themselves in the struggle. Above all, make them human! This leads us to the first of the four components of a radio play: Whether or not you select a frequently used place or period, you’ll still want to offer your audience a stimulating variety of characters-- people that you yourself would like to meet. Know their hopes and dreams. Make your villains as interesting as your heroes and heroines. Give your characters flaws as well as strengths. Perhaps a vicious gangster has a passion for classical music. Maybe an elegantly beautiful ballerina thinks she is really an ugly duckling. Most important, give your characters a goal-- something they want badly-- so badly that they will struggle against all obstacles until they either triumph or consume themselves in the struggle. Above all, make them human! This leads us to the first of the four components of a radio play:

Dialogue.

The dialogue introduces your characters, advances the action of the story, and brings it to the dramatic climax and eventual resolution. Also, since there can be no “stage directions”, as in a movie or play, such descriptions must be subtly worded into the dialogue. As you write your dialogue, keep in mind that each character has his or her own way of speaking. The words they use, the rhythm, the volume, and any accent are all points to ponder. Listen to the people you see around you wherever you go. Strive for vocal variety so that when your show is produced each voice will sound different to the listener.

Dialogue in a radio play is meant to be heard and not just read. Your job is to make it sound like two real people talking. You might try reading your dialogue out loud as you write it to see whether it sounds natural. Or you can have someone else read it to you. If it seems awkward then rewrite until you've got it right. Strive to keep speeches as short as possible. It is rare for one person to talk for five minutes while the other person stands there silently. Actual speech is often like short bursts between two individuals. And don’t forget to add reactions from any surrounding characters.

In addition, in radio, unlike a movie, you can’t see where the character is. His or her position can only be suggested by the placement of the actor in relation to the microphone. The writer, therefore, should add special words before or during a line of dialogue, which helps the actor or sound engineer create the illusion of position. The term ON-MIKE means the actor should stand right in front of the microphone to be in the center of a scene. It is only necessary to add ON-MIKE when the character has been OFF-MIKE previously.

The term OFF-MIKE means that the listener will “hear” that one character may be speaking to another from across the room. Other terms that are used include FADE IN; in which a sound engineer gradually brings up the voice of an actor. This is often used in opening a scene. A FADE OUT is just the opposite and is sometimes used to end a character’s dialogue as the scene closes. If you would like to hear superb examples of dialogue you may listen to such diverse radio shows as Gunsmoke, Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar, or The Jack Benny Program. This brings us to the second component of a radio play:

Sound Effects.

Just as you and I live in the real world, realistic radio characters live in their own environment. This is conveyed most effectively through sound effects. They may be as simple as an individual walking across a wooden floor or as complex as a fight scene between two characters. Sound effects personnel can create scuffling of feet, blows to stomachs, breaking of beer bottles over heads, or the finality of a gun shot.

Some sounds are momentary like popping a champagne cork. Some may last throughout a scene. An example of this is a jet plane as it flies towards a particular destination. The best way to handle these continuing sounds is to introduce them by FADING IN AND UP as the particular scene opens. As the scene continues and the characters start to speak, then add the term FADE UNDER, which lets your sound crew know to lower the volume so it doesn't interfere with the dialogue. FADE OUT ends the sound.

Use sound effects where beneficial to the script, but don’t overuse them. It’s not necessary to hear footsteps of characters in every scene. To see how some of radio’s finest experts handled sound, you can listen to Lights Out, Gunsmoke, or Dragnet. If you think of a great radio show as a banquet, then the dialogue is the meat and the sound is the seasoning. Every great meal deserves something to enhance the mood. Our third component fits the bill perfectly:

Music.

Music can be an integral part of your play and may fulfill many roles. Perhaps you would like to open your show with a memorable musical theme. This theme will help your audience understand what kind of show it will be. The music for a drama will sound differently than for a horror show or a comedy. If you are contemplating writing a continuing series, you will definitely want an unforgettable theme. Music can be an integral part of your play and may fulfill many roles. Perhaps you would like to open your show with a memorable musical theme. This theme will help your audience understand what kind of show it will be. The music for a drama will sound differently than for a horror show or a comedy. If you are contemplating writing a continuing series, you will definitely want an unforgettable theme.

There are also a variety of shorter musical passages or Cues to transition from one scene to another or to condense a long speech by suggesting the passage of time. Cues can be used to introduce a flashback and then bring the listener back to the present. They can also be used during a scene to convey the mood. Remember, don't overwhelm your listener. With practice you’ll develop a sense of where to use music most productively. Here again, a wonderful program to learn from is Gunsmoke, which had the highly talented composer, Rex Koury as its musical director.

So far we have discussed dialogue, sound effects, and music. We now turn to the fourth and final component of a radio play:

Silence.

Silence is often overlooked as a dramatic device; yet effective use can heighten the emotional impact of a scene. Think about a long pause as a character is stunned by what he or she has just seen. Perhaps another one is searching for just the right word to say. Silence can also be used as an alternative to music to separate two scenes. Let's return again to Gunsmoke, which often used silence to great advantage.

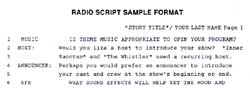

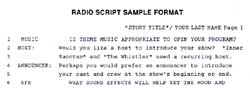

Now that you have an understanding of the importance of a good story and of the four components of a radio play, you are ready to begin the challenging but rewarding job of writing that script.  Take a look at the sample format (click on the image to your right) and adapt it for your own use. Then, when you’ve written and rewritten your script until you’ve made it the best you possibly can, you’re ready to get it produced. Take a look at the sample format (click on the image to your right) and adapt it for your own use. Then, when you’ve written and rewritten your script until you’ve made it the best you possibly can, you’re ready to get it produced.

Maybe you’d like to have it performed by members of your own Radio Club. Perhaps you’ll want to submit it to one of the various script competitions across the country such as the Friends of Old Time Radio Scriptwriting Contest. Maybe you’ll want to follow in Orson Welles’ footsteps and produce, direct, and star in your own productions to be broadcast on radio stations across the country!

Whatever you decide, I wish you the very best of luck and know that you too will experience the miracle of writing for radio!

Edgar Farr Russell, III is a writer, director, and actor whose work has appeared on National Public Radio, local cable television, and on stage. He is also a member of the Metropolitan Washington Old Time Radio Club.

|