|

This story was published in Radio Recall, the journal of the Metropolitan Washington Old-Time Radio Club, published six times per year.

Click here to return to the index of selected articles.

|

|

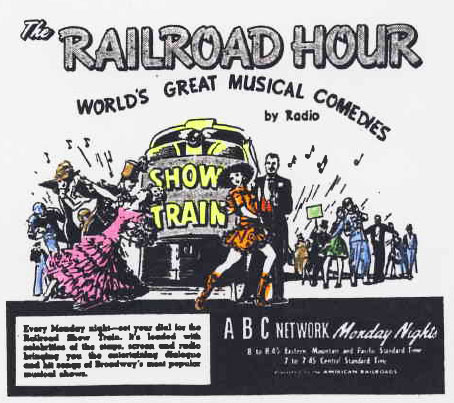

THE RAILROAD HOUR

(From Radio Recall,

October 2007)

by Martin Grams Jr. and Gerald Wilson © 2007

co-authors of the new book: The Railroad Hour

Published by Bear Manor Media, www.bearmanormedia.com

“Entertainment for all. For every member of the family – the humming, strumming, dancing tunes of the recent musical shows. For Mother and Dad – happy reminders of the shows they saw ‘only yesterday.’ And also, occasionally, one of the great and everlasting triumphs that go ‘way back before then.” “Entertainment for all. For every member of the family – the humming, strumming, dancing tunes of the recent musical shows. For Mother and Dad – happy reminders of the shows they saw ‘only yesterday.’ And also, occasionally, one of the great and everlasting triumphs that go ‘way back before then.”

This was how the Association of American Railroads described their product known as The Railroad Hour, in their annual publicity pamphlets. For 45 minutes every Monday night, over the American Broadcasting Company’s national network, the American Railroads presented for listener enjoyment, one after another of the world’s great musical comedies and operettas . . . the top-rated successes whose names had been spelled-out in the blazing lights on both sides of Broadway. Complete with music and words, the program offered famed headliners of the stage, screen and radio taking the leading roles.

Highly favored by Joseph McConnell, President of the National Broadcasting Company and William T. Faricy, President of the Association of American Railroads, The Railroad Hour competed against such radio programs as CBS’ high-rated Suspense and The Falcon in the same weekly time slot. The series lasted a total of 299 broadcasts over a span of six broadcast seasons – an accomplishment some would consider impossible by today’s broadcasting standards should the program be dramatized on television.

The Railroad Hour was broadcast from the studios of the National Broadcasting Company in Hollywood, California. The program was heard regularly over 170 stations of the NBC network. According to an annual report issued by the Association of American Railroads that it was estimated that the program was heard by more than four million family groups.

“Musical shows with a dramatic continuity are enjoyed by persons of all ages, especially when the leading roles are portrayed by outstanding artists. All members of the family, as well as school, church and club groups, find The Railroad Hour wholesome, dignified and inspiring entertainment,” quoted Van Hartesveldt.

So why is the program called the Railroad “Hour” when it was on the air only thirty minutes? In radio, the term “hour” was indicative of the time of the beginning of the broadcast, rather than the number of minutes the program was on the air. Also odd was the fact that the program ran a mere 45 minutes instead of 30 or 60 during the opening months. During its half-hour, The Railroad Hour gave its listeners 25 minutes of entertainment. About two-and-a-half minutes were given to the railroad message. The remaining time was required for opening and closing announcements and station identifications.

The Railroad Hour did not broadcast any operas, contrary to popular belief and reference guides. The producers of the series presented operettas and musicals, leaving the operas for other programs, namely The Metropolitan Opera broadcasts. The difference is that an opera consists of a dramatic stage performance set to music in which all dialogue is sung, rather than spoken. An operetta is a musical performance where the conversations are “talked” and the expressive moments are set in song.

One question came up during a standard question and answer session with the Association of American Railroads: “Are recordings of The Railroad Hour broadcasts available?” The formal answer from the Association was that copyright restrictions did not permit the producer of The Railroad Hour to make any recordings of the musical program. However, recordings of many of the song hits heard were available at music stores. This of course, was the formal public statement.

In reality, every broadcast of The Railroad Hour was recorded and transcribed. Numerous copies were made for both legal and historical purposes. Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee, who wrote the majority of the scripts, actually kept a copy of almost every broadcast for their personal collection. These discs were later donated to the Billy Rose Theatre Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts located at Lincoln Center in New York City. The Library of Congress presently archives copies of all the discs.

Dealers and collectors specializing in recordings from the “Golden Age of Radio” have come across similar depositories over the years and thankfully, more than half of the broadcasts are presently available from dealers nationwide. Marvin Miller, the announcer for The Railroad Hour, saved a few of the scripts, which were later donated to the Thousand Oaks Library in California. A limited number of free admission tickets for the public were available for each Railroad Hour broadcast. Tickets could be obtained by writing to the Association of American Railroads, Transportation Building, located in Washington, D.C., or by writing to the National Broadcasting Company in Hollywood, California. The Applicant was required to give the date for which the tickets were desired and the number of persons in the party. Because of the demand for tickets (especially since they were free), the public had to request them weeks in advance of the broadcast.

From the 1948 annual report of the Association of American Railroads: “Beginning on October 4, 1948, the AAR produced and presented a weekly coast-to-coastradio program entitled “The Railroad Hour.” Broadcast on Monday evenings, the program haspresented condensed versions of outstanding musical comedies and light operas with Gordon MacRae as singing host and master of ceremonies and featuring top-name guest stars.”

AAR President William T. Faricy delivered a message on the show’s premiere episode, expressing his pride and joy for the presentations that are planned, and the hope that the radio listeners would tune in each week for future presentations. The premiere broadcast featured Jane Powell and Dinah Shore in the cast. In Good News, the plot about a football hero who has to pass an important exam so he can play in the big game, and please the girl he loves, inspired a slew of imitations on stage and screen. But none could match the infectious score composed by Ray Henderson with lyrics by Buddy Desylva and Lew Brown.

Their dance-happy songs included “The Best Things in Life are Free” and “The Varsity Drag,” a Charleston-style dance number that became an international craze. The libretto was a fairly loose affair, allowing members of the cast to offer audience pleasing vaudeville-style specialties. The author of the radio adaptation was none other than Ed Gardner, creator and star of the situation comedy, Duffy’s Tavern. This would be his first and only contribution for The Railroad Hour.

The October 5, 1949 issue of Variety reviewed the second season opener:

“The Railroad Hour is back on the air with its winter season of operettas and musical comedies, to add a lush, melodious half-hour of better-grade American music to Monday evening’s listening. With first-rate artists, good supporting choral and instrumental ensemble, and top direction and production, airer has flavor and appeal.

“Monday’s preem was the perennial favorite, ‘Show Boat.’ Done in dialog as well as song, the Hammerstein-Kern musical retained all of its nostalgic charm and rich melody. Gordon MacRae, who was sort of emcee as well as male singing lead, acquitted himself quite creditably, with the Met’s Dorothy Kirsten and Lucille Norman giving admirable support. Chorus under direction of Norman Luboff, and orch under Carmen Dragon, added to the smooth proceedings.”

Regrettably, the final two seasons of The Railroad Hour featured very little highlights worth mentioning compared to the program’s first season. Repeat performances of musicals performed previously on the show became more common towards the end of the program’s run. In fact, of the 38 episodes broadcast during the program’s final season, 28 were repeats.

The Railroad Hour was tied with Dr. Christian as the 19th highest rated show of the 1952-53 season, making the program at this point, still one of the top twenty programs of the year. For the 1953-54 season, The Railroad Hour was tied with Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar in 14th place!

The final broadcast of The Railroad Hour was on June 21, 1954. The reason for the program’s termination remains unknown, and the Association of American Railroad’s Annual Report of 1954 sheds very little light except for a brief mention: “The Railroad Hour, consisting primarily of condensations of outstanding operettas and other musical shows, was presented in 1954 for a 30-minute period each Monday night over the full network of the National Broadcasting Company through June 21, 1954, when the program was discontinued.”

During the early 1950s, the Armed Forces Radio Service offered rebroadcasts of radio dramas for troops stationed overseas. Many of the Railroad Hour presentations were rebroadcast, as part of the network’s Showtime line-up. Most references to the Association of American Railroads was deleted from the rebroadcasts, as sponsorship was often disregarded as important when it came to entertaining the troops. Shortly after, the AFRS featured rebroadcasts of The Railroad Hour under a new name, The Gordon MacRae Show, using the song “I Know That You Know” from MacRae’s film Tea for Two as the theme. Many of these recordings circulate among collector catalogs.

Although a recording for every Railroad Hour broadcast does exist in air check form (as they aired back in 1948-1954), collectors do offer a number of recordings from the AFRS rebroadcasts. Regrettably, those edited, “washed out” versions are not as enjoyable as the original offerings. The musical presentation is intact, but much of the flavor of the series, including the Railroad commercials and cast comments, make up some of the program that makes these shows so special. The authors of this article recommend that the readers make an attempt to acquire and listen to the uncut recordings and avoid the AFRS rebroadcasts if at all possible.

Throughout their careers, Lawrence and Lee continued to write and produce radio programs for CBS. They co-wrote radio plays including The Unexpected (1951), Song of Norway (1957), Shangri-La (1960), a radio version of Inherit the Wind (1965), and Lincoln the Unwilling Warrior (1974).

In 1954, one of Lawrence and Lee’s original one-act operas, Annie Laurie, was published by Harms, Inc., who specialized in publishing music in various forms across the country. The musical was adapted from Lawrence and Lee’s original Railroad Hour script. For the next two years, Harms, Inc. published two more original musicals, Roaring Camp (1955) and Familiar Strangers (1956), also previous Railroad Hour originals.

Having admired the prestige received on The Railroad Hour, announcer Marvin Miller saved a few scripts from the series for his personal collection. During the early-1980s, Miller donated a total of 47 linear feet of scripts and correspondence, 135 open-reel audio tapes and eight scrapbooks covering his work in radio, film and television to the Thousand Oaks Library in California. Today, the Marvin E. Miller Collection is available for viewing by any patron who chooses to personally visit the library during open hours.

The Thousand Oaks Library, however, is not the only place where fans of The Railroad Hour can find access to scripts, recordings and other materials related to the program. The Western Historical Manuscript Collection at the University of Missouri – St. Louis has made their American Radio Collection available for the public. Donated to WHMC by the Thomas Jefferson Library at the same University, the archive holds a number of episodes in their archives.

The Billy Rose Theater Collection located at the Lincoln Center of Performing Arts in the New York Public Library holds the Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee Collection, which includes a broad sampling of the material that the team created for radio, television, and the stage. Included in the collection are complete holdings for The Railroad Hour, both recordings and scripts. These include almost the entire run of The Railroad Hour, all off-line recordings from KFI in Los Angeles, California. Each recording is complete on two sound discs, analog, 33 1/3 RPM., 16 inch aluminum-based acetate discs. Access to many of the original items (such as transcription discs) is restricted at the Library. Many of the broadcasts, thankfully, have been transferred to sound tape reels (analog, 7.5 IPS, 7 in.) so patrons can listen and enjoy the musicals. In 1967, they presented a full collection of Railroad Hour recordings to the Rodgers and Hammerstein Archives of Recorded Sound at the New York Public Library.

The Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee Collection may or may not be complete. According to their inventory, the collection holds a total of 532 sound recordings – not all of them are The Railroad Hour. While the archive does house one rehearsal recording, the list of titles and broadcast dates remain incomplete. As described by the library’s catalog system: “The Railroad Hour was a half hour music and drama program broadcast on NBC from 1948 to 1954. It featured musical comedies and original stories complete with music. Gordon MacRae was the host and featured star, and was assisted by such performers as: Dorothy Kirsten, Jeanette MacDonald, Adolphe Menjou, Risë Stevens and Margaret Whiting. Dorothy Warenskjold and Lucille Norman often stood in for Gordon MacRae during the summers. The announcer was Marvin Miller. The theme song was I've Been Working on the Railroad.”

Comparing the library’s inventory with the recordings known to circulate among old-time radio collectors, it is estimated that about six recordings remain unaccounted for. Dismal hopes should not prevail, as it is “assumed” (but not proven) that the Lawrence and Lee Collection does contain a recording of every broadcast – and that the inventory sheets are merely incomplete.

Many of Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee’s scripts, manuscripts, drafts and personal papers were donated to the Ohio State University a number of years before their death, and though available for public viewing, are not available for inter-library loan. Anyone wanting to see what a script for The Railroad Hour looks like, or a theater ticket for general admission, can easily contact the library for operating hours.

Lastly, the Library of Congress currently owns copies of all of the scripts on microfilm, available for viewing by anyone willing to register with their library system and adhere to the strict guidelines and policies for viewing the scripts. Still, being a musical program, the scripts are not a feasible substitute for enjoyment of these nostalgic broadcasts. To truly enjoy the presentations, readers are encouraged to purchase copies of these radio programs from respectable dealers who have been in business for decades, and were responsible for originating the recordings presently available.

|