THE MUSICAL STEELMAKERS:

RADIO'S FIRST ALL EMPLOYEE BROADCAST

By Jim Widner © 2007

(From Radio Recall, October 2007)

On Sunday, November 8, 1936 in the large studio of radio station WWVA on the top floor of the Hawley Building in Wheeling, West Virginia, a historical broadcast was about to take place. In the control room sat a slightly balding, bespeckled advertising executive for the Wheeling Steel Corporation named John L. Grimes. He was about to see his creation come to fruition after six years of trying to convince company executives that this broadcast was a good idea.

It was 1:00 in the afternoon and the broadcast was the premier of a musical variety program called “It's Wheeling Steel.” Though the networks and major advertising companies controlled much of what was heard over the radio during mid-1930s, there were still many smaller radio stations producing their own programming under the sponsorship of local area companies. But what made this broadcast of historical significance is that it was the first of its kind using only the talents of employees of the sponsor's own company. The producers, writers, musical arrangers, and performers all worked in the steel mills and offices of the Wheeling Steel Corporation during regular hours and in their spare time as a part of this broadcast production.

The idea for a musical program began to germinate in the mind of John L. Grimes in 1930 when he realized that he could produce a weekly half-hour radio show for one month for the same cost of advertising in a national magazine such as The Saturday Evening Post. Radio, he observed as an advertising professional, was fast becoming a major vehicle for spreading the word about a company's product. Already seventy percent of all homes in the United States had at least one radio. Major sponsors such as Amos 'n' Andy's Pepsodent and Jack Benny's Jello were reaping the benefits of radio. But when Grimes went to company executives with his idea, they balked. They questioned the value of advertising their steel products over the radio. It was fine for consumables such as toothpaste and foods, but they did not see value in advertising their products to the mass consumer.

What Grimes proposed was more than just advertising the company's production output. He felt it was a good idea to promote both the product and the employees who created the product. He pointed out to the executives how he had previously used the employees' musical talents to help promote company products to farmers. At the National Cornhusking Championship in Marshall, Missouri, employee Lou Salvatore's Novelteers, a musical ensemble composed of employees of the company, performed as well as promoted Wheeling Steel's COP-R-LOY farm fencing among other products. But more than that, the broadcasts would be good for company morale. In a time when the Great Depression was at its worst, and employee loyalty was needed more than ever, company pride was imperative for continued success.

By the summer of 1936, Grimes finally got the go ahead to pull together a trial broadcast. With the help of WWVA program director, Walter 'Pat' Patterson, Grimes began auditioning talent. There was one hard and fast rule that he required: everyone connected with the show's production and performance had to be employees or immediate relatives of employees of the Wheeling Steel Corporation. Throughout the history of the show, Grimes never wavered from this rule.

The format would be a thirty-minute musical variety with a regular orchestra playing musical numbers, choral and individual singing and at least one 'headliner.' The headliner would be a stand out employee performing as guest on the program. Initially, Pat Patterson would help Grimes with the show providing his broadcast expertise, and, of course, the facilities of WWVA. At one point in the broadcast, facts about Wheeling Steel would be presented as the commercial side of the program. But throughout the whole time on the air, it would be emphasized that it was a broadcast of the Wheeling Steel family.

In the mid-1930's Midwestern musical tastes were becoming more eclectic with the increasing popularity of radio. The popular musical shows still included Grace Moore and Lawrence Tibbet, both operatic singers. But choral music as that of Fred Waring was also becoming a staple.

The format for the first year of “It's Wheeling Steel” included the Musketeers, a vocal group comprised of mill workers and employee relatives whose music tended toward the nostalgic sweet strains of religious themes. There was also the Steelmakers Quartette, a barbershop quartette, and stenographer Sarah Rehm billed as the “Singing Stenographer”. The music they performed also included light classics and popular show tunes of the period. The production was very straightforward with little, if any, banter but only the introduction of acts and the promotion of the Wheeling Steel Corporation products by the Station Manager, Pat Patterson.

With the Station Manager's help, Grimes was able to engage the cooperation of radio station WPAY in Portsmouth, Ohio to also broadcast the show (Wheeling Steel had plants in Portsmouth). This allowed listeners all along the Ohio River to hear the show. It was an instant success especially among Wheeling Steel's own employees. The homespun feel of the production with “real” people performing made the whole area proud of Grime's creation. Employee's and relatives flocked to try out. The advertising executive found he had more acts to choose from than he could place on the air.

Partly due to its success and the desire to accommodate a live audience, the show was moved for its second season to the Wheeling Scottish Rite Cathedral stage with a larger orchestra where it was billed as an “All Employee Broadcast.” The format of the show became a little less formal as one prominent character began to emerge - the Old Timer, who was portrayed by the company's auditor, John Winchcoll. The “Old Timer” character served as a foil for the others on the show as well as providing gentle banter as he introduced the acts.

THE NATIONAL STAGE

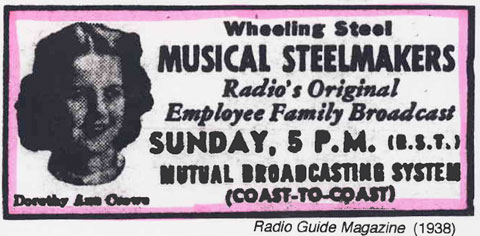

By December 1937, the show was so successful that John Grimes, whose production work was virtually a full-time job, decided to try taking the program into a more national venue. Having convinced his employers to spend money on a test slot of the Mutual Broadcasting System's 17 radio stations, the program premiered on January 2, 1938, a Sunday, at 5:00 PM. Billed now as a national broadcast, the acts sounded more professional and the music reflected a lot of the popular music of the time.

In order to keep the quality high, Grimes would work out deals with those who had professional backgrounds. In order to keep his rule of remaining a Wheeling Steel Family, agreements would include hiring the performer to “work” at the Wheeling Steel offices, while spending ample time on the program. One such example was Regina Colbert, a fine singer, who was hired to work as a secretary in the advertising department.

This and subsequent broadcasts were instant hits over the “national” Mutual network. Life Magazine wanted to do a photo shoot of the production and personnel. Radio Guide Magazine featured an article about them as did Billboard and others. The participants were fast becoming national celebrities.

As the production continued to become more polished, it also began a move to a new location. Leaving the Scottish Rite Cathedral behind, it first moved to the Market Auditorium and then finally settled into the Capitol Theatre by 1939. Well-known bandleaders took an interest in the show. On a later one, Paul Whiteman even was heard conducting the orchestra! The Capitol afforded lots of room both for the production as well as for the audience. The acoustics were much better and the broadcast began to sound even more polished.

Some of the early performers, amateurs all, included Dorothy Ann Crowe, a terrific soprano, Arden White (who later married Dorothy) who was one of the first male soloists. Arden was one of the rare employees who had musical training though he worked in the advertising department at Wheeling Steel. Another standout was instrumentalist Verdi Howells, who was a machinist by day. “Pop” Grimes, as he was known to the performers and production staff, explained once that much of the talent was due to the number of Welsh bred descendants. The Welsh, known for their musicality, settled the area in the late nineteenth century mostly to work the mines and mills of West Virginia.

The next momentous time for the program came in October 1941. The show was picked up by the National Broadcasting Company's Blue Network. Truly it was a national network program; even larger groups of listeners were added to the already swelled numbers. With NBC, stricter censorship of the program became the norm, mostly because of the songs. In one telegram from the network giving authorization to use a song it read “Addition of 'Army Air Corps' approved. If vocal, please substitute terrible for helluva.”

As the country moved toward looming war, the productions took on a more patriotic theme. The popular songs of the day were featured and performed by various singing groups including the Steel Sisters (Lois Mae Nolte, Harriet Drake and Lucille Bell) and the Evans Sisters (Betty Jane, Margaret June and Janet Jean). In a sign of the increasing popularity of the employee/performers, the Evans Sisters replaced the Steel Sisters who went on tour with Horace Heidt and his Orchestra.

The Steel Sisters as featured on It's Wheeling Steel.

WAR LOOMS

On December 7, 1941 the program was set to go on the air at 5:00 P.M. Eastern Standard Time. The theme of the show that day was “Blues on Parade.” The familiar opening began:

“You hear now from historical and industrial Wheeling...the original employee family broadcast direct from the stage of the Capitol Theater...in Wheeling, West Virginia...and there goes the mill whistle.” This was followed by the familiar sound of the steel mill whistle calling the workers to the plant. Immediately, the program moved to its first musical number - Blues on Parade. Throughout the broadcast references are made to “defense workers during the week, your aspiring young entertainers on Sunday” and a “red, white and blues program.”

Near the end of the broadcast the Old Timer in a burst of patriotic spirit starts the close of the show by referencing the daughter of one of the employees who appeared in a child role in the Bing Crosby film “Birth of the Blues.”

“And only here, in America, do we find the 'Carolyn Lees' because only here does Opportunity extend his clean hands to welcome the young and old alike to careers of their choice and for which they are especially fitted, regardless of race or creed.”

According to former members of that broadcast, it was believed that the program never went out over the air due to the attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor. But NBC Master Logs dispute that showing that the program was only pre-empted in New York when Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia interrupted to give guidance to New Yorkers after the attack was announced. The logs show that NBC did release the program for broadcast over their network.

Though the show went on the air only a few hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor began, the performers were well aware of the events. The script was pretty locked down due to musical numbers and timing, but one change on the script that day showed their concern. The original final monologue by the old timer included the line: “Sure, here we have something different and vastly better; something to defend, to protect and perpetuate for our children and our children's children...for all the Carolyn Lees and their brothers of tomorrow. That's why, friends, the Old Timer reminds you of Defense Bonds and Savings stamps.”

The last two sentences were crossed out and these words added: “You've heard the radio this afternoon - it’s serious business - our boys and you're boys are in jeopardy. Buy Defense Bonds and Savings stamps now!!”

World War II changed the tenor of the show through to its final broadcast. When the war began, backroom discussions on whether the show should continue were initiated. Some executives preferred the show be canceled or at least suspended during the duration; cooler heads prevailed, however, arguing that the esteem the company had built along with the morale factor in supporting the war effort were invaluable for maintaining its schedule.

The image of one American company supporting its war effort became the center focus of subsequent broadcasts. The program began a series of shows with a “Buy a Bomber” theme airing from selected cities in West Virginia during 1943. The host communities were challenged (as were the listeners) to buy enough Defense Bonds to purchase a medium-sized or large bomber. Successful cities would see those bombers going into battle with the town's name on the plane.

By 1943, the show was at the peak of its national popularity reaching fifth place among the NBC lineup. Letters would pour in from soldiers around the country and overseas: “I wonder if all of you know how it made a lonesome man feel, somewhere out in the Pacific, when he heard the Steelmakers come over the air Sunday night?”

September 1943 marked the start of the show's eighth season on the air. The war was just beginning to come out of its lowest ebb and the end seemed possible. Unfortunately, the health of its creator and guardian angel, John Grimes was beginning to decline. His drive was ebbing and there was no one who seemed able to take on the many hats he wore. The final broadcast of “It's Wheeling Steel,” its 326th was heard on June 18th, 1944. Many who appeared on the program went on to bigger careers appearing with major entertainers such as Perry Como, Lawrence Welk and many of the Big Bands of the time.

But the legacy of the Musical Steelmakers would live on. The program had indeed been a pioneering one demonstrating how corporate relations and industrial advertising could produce a remarkable series. There were other examples from the age of radio, but nothing like this would be heard again where “men of steel became men of entertainment.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jim Widner is the author of Science Fiction on Radio: A Revised Look and of numerous other articles on the history of radio drama. His web site, Radio Days www.otr.com currently in its 12th year is devoted to the history of radio entertainment.

|