DOC HERROLD: THE FATHER OF BROADAST RADIO DOC HERROLD: THE FATHER OF BROADAST RADIO

By Marty Cheek © 2008

(From Radio Recall, April 2008)

EDITOR’S NOTE: Charles “Doc” Herrold, despite his great contributions to radio broadcasting in the early 1900s, is virtually unknown today, even to many in the OTR community. Marty Cheek corrects that deficiency in this informative article, which first appeared in “The Gilroy Dispatch” of Gilroy, CA 95020 and is reprinted here with the permission of the author.

Born in Illinois on Nov. 16, 1875, Charles Herrold moved as a boy to Santa Clara Valley and grew up on his family's San Jose farm. His young and inquisitive mind set upon creating new inventions. One of his earliest was a clock-driven telescope that held aim at the stars during astronomical observations.

After graduating from high school, Herrold attended Stanford University and studied physics and electricity. "Wireless" technology was still in its infancy, developed in 1895 by the Italian Guglielmo Marconi whose invention "telegraphed" messages over the airwaves.

Herrold, however, saw a greater potential for radio waves than just a medium for sending the dots and dashes of Morse Code across the distances. He believed voices and music could also be transmitted. The radio pioneer saw the future potential.

With ambitions of fame and fortune, in 1900 Herrold founded an electrical manufacturing firm in San Francisco. Things went well until 1906 when a rather major earthquake hit the Bay Area early one April morning. Herrold lost everything but his dream.

He headed to Stockton to teach at a state technical college for a couple of years, then made his way back to San Jose in 1909. Here, he set up his electronics academy — the Herrold College of Wireless and Engineering. Students called him "Doc."

Although his name is not as famous as Marconi's, Doc Herrold's work did add several significant contributions to wireless innovation. He built a spark gap transmitter attached to a carbon microphone. With this experimental device, he and his college's students were able to send out relatively low frequency 50-watt transmissions from San Jose's seven-story Garden City Bank Building. (The Knight Ridder Building now occupies the downtown spot where it once stood.)

In those days, wireless technology was still in its infancy. So Herrold and his students had to spend their spare hours building simple crystal radio receivers for listeners to pick up their transmissions. Local folks were astonished to hear the words "This is the Herrold Station" and "San Jose calling" on the bulky receiver headsets they wore. The moment must have seemed magical for many.

Unfortunately, Herrold's early transmitting device had a major headache. The carbon element burned out every couple of hours. Replacing it cut into transmission time. So, Herrold came up with a new transmitting contraption he called the "Arc Fone." It was a series of six arc lights which generated high frequency radio waves strong enough to carry voices and music longer distances.

The power-hungry Arc Fone required far more than 50 watts — the power of a light bulb. So Herrold "borrowed" the 500 volts he needed from San Jose's streetcar line. He had to water-cool his microphone to keep it from incinerating.

In 1910, Herrold became the first broadcaster to play music across the airwaves on a regular basis. He made a "trade-out" deal for records with San Jose's Sherman Clay music store. He played songs such as "My Old Kentucky Home" on a wind-up Victrola phonograph pointed at his crude microphone. He even became the first person ever to take song requests over the phone.

Herrold also pioneered radio contests presenting prizes to reward loyal listeners. And he became the first to broadcast current events and weather reports over his wireless station, setting the format for today's radio and television news. He also came up with the concept of radio advertisement — commercials breaks — to pay for this exciting new technology.

Starting in 1912, Herrold's wife Sybil Herrold became the first female disc jockey. Her "Little Hams" program was aimed at getting children involved in the radio experience.

Herrold's wireless transmissions could be heard all over the Bay Area including in Morgan Hill, Gilroy and Hollister. In 1915, he transmitted music from San Jose to the Panama Pacific International Exhibition in San Francisco, giving amazed attendees at that world's fair a taste of the technology.

In April 1917, the United States entered the Great War in Europe. For national security, Uncle Sam prohibited all non-government wireless transmissions. During the war years, Herrold's Arc Fone became obsolete when Lee DeForest introduced his Audion tube — a more innovative technology that eventually led to computers.

In 1921, Herrold rebuilt his San Jose station. The government assigned it the call letters KQW. Facing hard financial times, he sold the enterprise in 1925. He stayed on as station engineer for a time until he was fired.

Herrold's last years were marked by a series of humble jobs such as a security guard. He died on July 1, 1948, never truly enjoying the recognition he deserved as a genuine pioneer of radio.

Today, the term "wireless" is a technology buzz word again — this time connected to the Internet. Wireless is the next stage of high-tech's evolution. It'll soon be common for laptop computers to have widespread mobile connections to the vast ocean of World Wide Web information.

Here in the South Valley, people like Jim Carrillo see the potential of of wireless Internet connection. Modeling Herrold's first radio commercials, Carrillo's innovative Morgan Hill-based company, Public Wi-Fi Project, sells advertisements to pay for the regional development of wireless Web technology.

Some historians consider Charles Herrold to be "the father of broadcast radio." Although now virtually forgotten, his impact continues to spread like the radio waves he loved. Remember his San Jose station KQW? Well, in 1949 it moved to San Francisco. The call letters changed to KCBS.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Marty Cheek is a regular columnist for the Gilroy Dispatch and is the author of "The Silicon Valley Handbook."

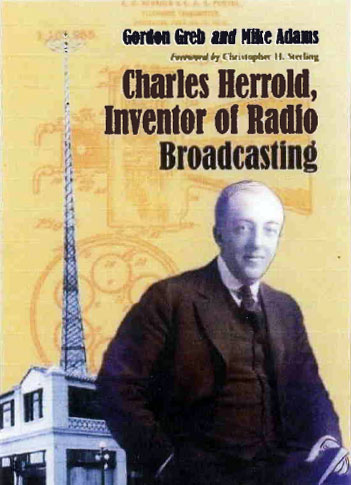

ADDENDUM: To learn all about the life of Charles “Doc” Herrold and his total contributions to the emerging radio broadcasting medium, you can read his biography, written by Gordon Greb and Mike Adams, published by McFarland in 2003. It has 259 pages, 72 historical photographs, and it retails for $45 from most Internet dealers.

|